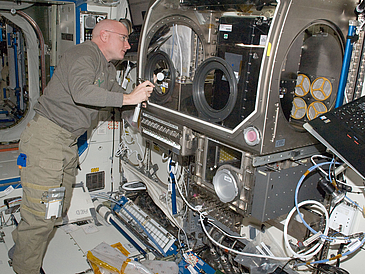

Today, a team of scientists from the Center of Applied Space Technology and Microgravity (ZARM) at the University of Bremen started a second series of experiments on board the International Space Station ISS. The excitement at the institute matches what was felt during the first series in January 2011. The ZARM scientists at ground control are able to observe the astronauts on board the ISS setting up the experiment, and the experiment itself is remotely controlled from ZARM. The international team comprises four ZARM scientists and a team from the Portland State University (PSU). The project, which is funded by the German Aerospace Center (DLR), is also supported by NASA.

The purpose of the first experimental phase was to investigate the capillary behavior of fluids under conditions of microgravity. To be more precise, the experiments show which parameters influence the flow of a liquid through capillary channels and how this liquid can be protected from gas ingestion (choking effect).

This time, the channel geometry has been changed, and gas bubbles can be injected into the flow. Besides this investigation of the stability of this new channel, the scientists are interested in how the bubbles, formed by gas ingestion can be transported back to the surface and subsequently separated from the fluid. The practical value of the research findings lies in the handling of fluids in space, like fuel, for instance. In the tanks of satellites and space vehicles the fuel does not accumulate at the bottom of the tank – like it would on Earth – rather, the absence of gravity means that it is free to spread all around the tank and other components. This makes it necessary to have some sort of system to ensure that the fuel is directed to where it is needed. The general aim of the experiments is to shed light onto how fluids can be transported free of bubble formation with the aid of capillary channels.

The experimental set-up on board the ISS is fitted with channel geometries of the type normally used for handling fluids in space. In order to take up the fluids and bind them by use of capillary forces, the channels must at least have one free surface. The current set-up incorporates a wedge channel. The fluid flowing through it develops special flow profiles which can facilitate the removal of gas bubbles from the fluid by transporting them back to the surface.

Further information:

Birgit Kinkeldey

Phone.: +49 421.218 4801

E-Mail: birgit.kinkeldeyprotect me ?!zarm.uni-bremenprotect me ?!.de

www.zarm.uni-bremen.de