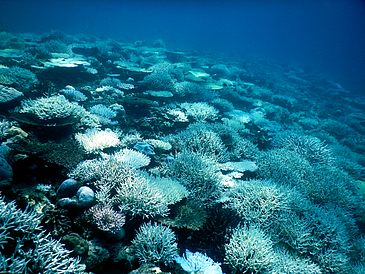

The warming of the oceans due to climate change and the subsequent increase in frequency and severity of coral bleaching are the worldwide biggest threats to coral reefs. Thus, how quickly coral reefs can recover from such bleaching is of great interest and the number of young corals provide a good insight. Researchers involved in an international research project within the Marine Ecology group at the University of Bremen and investigated this matter together with the Seychelles Islands Foundation (SIF) based on an isolated atoll in the Indian Ocean - with promising results. Within four years after the coral bleaching of 2016, the number of young corals multiplied two to threefold when compared with the situation directly after the bleaching.

“Much like adult corals, juvenile corals may be severely affected by bleaching and die. However, one type of coral bleaching also affects adult corals’ ability to reproduce. This means that the multiplication and thus the number of young corals may remain suppressed for several years after bleaching,” explains Professor Christian Wild, head of the Marine Ecology group at the University of Bremen.

Dr. Anna Koester, who recently completed her PhD at the University of Bremen, is the principle author of a study that has been published in “PLOS ONE” journal. The marine ecologist says: “The rapid increase in young corals that we have observed in the four years after coral bleaching is a good sign that the reefs of the Aldabra Atoll are recovering and it also fits well with our previous work.”

The Aldabra Atoll is one of only 50 marine UNESCO World Heritage Sites and lies far away in the Indian Ocean. Human-based, local factors, such as the input of nutrients or overfishing, play basically no role there, explains the scientist. However, the last case of coral bleaching in 2016 caused around two thirds of the corals to die. Thus, it is the ideal place to find out how the condition of damaged reefs changes when they is no exposure to any stress factors directly caused by humans.

In order to gain a basic understanding of the reproduction of corals at the Aldabra Atoll, researchers also took a closer look at the settling of coral larvae as part of the study. “Our findings suggest that coral spawning mainly takes place between October and December at the Aldabra Atoll. That is important information for further studies that investigate which reefs in the region contain coral larvae from Aldabra and thus also profit from Aldabra’s protection,” states Koester.

“Due to climate change, we expect there to be an increase in frequency of coral bleaching. This means that the period for reef recovery between coral bleaching occurrences will become continually shorter,” emphasizes Wild. Reducing the triggers of coral bleaching, especially the increase in ocean temperature, is therefore essential, as even isolated and strictly protected reefs, such as the Aldabra Atoll, will otherwise not have enough time to recover soon.

Further Information:

Study: Koester, A., Ford, A. K., Ferse, S. C. A., Migani, V., Bunbury, N., Sanchez, C., and Wild, C. 2021. First insights into coral recruit and juvenile abundances at remote Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0260516. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260516

Link to the study: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0260516

Marine Ecology group: https://www.uni-bremen.de/en/marine-ecology

Seychelles Islands Foundation: https://www.sif.sc

Contact:

Dr. Anna Koester

Email: anna.koesterprotect me ?!uni-bremenprotect me ?!.de

Prof. Dr. Christian Wild

Email: christian.wildprotect me ?!uni-bremenprotect me ?!.de